You’ve Only Got to Look at VAERS . . .

Our brains, just like our bodies in general, are impressive designs. So much so, we’ve only scraped the surface when it comes to understanding how they really work.

In the complex modern world, though, sometimes those things the brain is good at can also be disadvantageous.

One example of this is its ability to recognise patterns. If you study the social sciences at all, you will probably learn about stereotypes. To many people, “stereotype” is a dirty word, but in reality it’s the way our brains remember and categorise things, to stop us from going nuts.

It comes down to patterns. Our five senses take in so much information at any given minute that our brains would be overwhelmed if we were conscious of it all. So, very much in layman’s terms (as I’m not a neuroscientist), the brain uses pattern-recognition to make sense of things.

As a very broad example, if I’m walking down a dark alley at 2 am and I see a very tall, solidly-built guy with a bald head, a grumpy expression and a million tattoos walking towards me, flicking a switchblade, my brain will stereotype him immediately, saying, “Hang on, I’ve seen this movie before. This ends badly. Warning! Warning! Avoid! Avoid!”

In creative writing, you’re taught that minor characters will often be stereotypes for a reason – you probably don’t need to know that the petrol station attendant who takes the hero’s money was born in Philly, raised in Uganda, loves pugs and his five aunts, and has six toes on his right foot and a Swedish girlfriend. You just need a quick sketch of him that allows the brain to say, “Yes, I know that type of guy” and move on to the important bits.

Unfortunately, this fantastic ability to recognise patterns in things and categorise them accordingly comes with at least one disadvantage (aside from the obvious one – prejudice). That is, its wont to see patterns where there are none. When we’re talking about maths and science, especially when statistics are involved, this can cause huge problems.

You’ve undoubtedly heard the phrase “correlation does not imply causation”. Here is an example of correlation: let’s say that on weeks when I have more work, I get less writing done – those two things would therefore be correlated, or associated, with one another. That’s a pretty clear example, and our brains will make that leap between the two facts and reach a conclusion – if I have more work in a particular week, I have less energy and time to do my own writing. Makes sense. Many times, that conclusion will be correct. But what are we leaving out? Personal choice, for one. I may actually have plenty of time and energy to do both my work and the same amount of writing as usual, but I choose not to write on the weeks I have more work, because I can’t get into the “creative flow” as easily when I’m thinking about other things. If you were a scientist observing my behaviours, that’s one thing you would have to take into consideration. Still, the conclusion is the same: more work causes less writing. But what about if I have just lost a loved one? I’m also unlikely to do as much writing because I’m distracted by funeral arrangements, my emotions, etc., etc. So, what we can’t accurately say is, “Dan didn’t do as much writing this week; she must have had more work on.” In that case, although the amount of work I do is inversely correlated with the amount of writing I do, work was not the causational factor – my loved one’s death was.

You see how complicated this can get.

A real-world example is lung cancer. It was found that people who drank more alcohol were more likely to die of lung cancer, but scientists later realised that was because people who drank more alcohol were also more likely to smoke or passively smoke – and so the smoking is what’s called a “confounding factor”. The correlation between alcohol and lung cancer does not mean that alcohol causes lung cancer. Therefore, correlation does not equal causation.

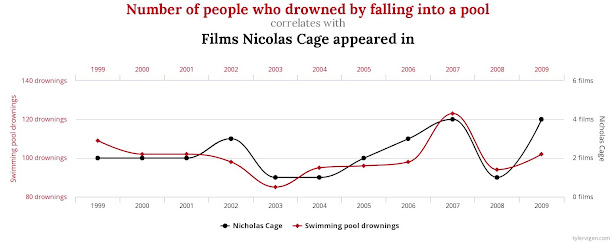

The most famous example of this is the correlation between Nicolas Cage appearing in movies and the number of people who fall into pools and drown:

Or my personal favourite, arcade usage = computer science doctorates:

Correlation, not causation.

Which brings us to those pesky vaccine inserts and – horror of horrors – the VAERS website.

Unfamiliar with VAERS? It stands for Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System. It’s run by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (the “CDC”) and the US Food and Drug Administration (the “FDA”) in the US. It’s a place where, literally, any man and his dog can report an “adverse event following a vaccination”. It’s passive, uncontrolled and unverified data. Some of it is made up. As such, it should never be looked upon as evidence of any kind. Its sole purpose is as an early-warning system. If scientists run an algorithm over the data and see, for example, the words “blood clot” appear more than would be expected in the general population, they can begin a proper clinical trial to discover whether the vaccine does, in fact, have a risk of blood clots associated with it – which, as we now know, the AstraZeneca COVID vaccine does have in certain cohorts.

One objection to this point of view is that doctors are adding many of these reports. That’s true, but they are required to report all adverse events within a certain time period after a vaccination no matter whether or not the vaccination caused the event. So, someone may have advanced coronary disease and have a heart attack four days after their COVID vaccination – their doctor will have to report that, but that doesn’t mean the vaccination caused the heart attack.

(I’ve thus far left out the fact that the same people who use VAERS as “evidence” of the dangers of COVID vaccines are the ones who say, “You can’t trust the CDC or the FDA” – not realising that the CDC and the FDA run the VAERS website.)

It’s the same on the much-touted vaccine inserts. Any illness that occurs to a trial participant during the trial of a medication will be recorded on the insert as a risk, even if that medication is not likely to be a causational factor. That’s why practically every medication says it “may cause” headaches, nausea, vomiting, etc., etc. – because millions of people experience those ailments every day.

There has to be, at the very least, a plausible biological pathway for these things. Next time someone tells you that their applied kinesiology practitioner discovered they were low on Vitamin D, ask them how. They will tell you that he/she placed a bottle of Vitamin D in a box, held it to their skin, and then tested their muscle strength. If they can explain to you how the body “knows” what is in the box/bottle, they’ll say it comes down to “energy” or “frequencies” or some such nonsense. In other words, there is no logical biological pathway for this type of diagnosis. It’s witchcraft.

It’s the same with claims of adverse reactions to vaccines. If there’s not even a plausible biological pathway for the reaction claimed, it’s bogus. The person might truly believe it was caused by the vaccine, but they’re wrong.

People get sick all the time. They also drop dead all the time, for various reasons – heart attacks, strokes, aneurysms, etc. – and for no detectable reason. Statistically, therefore, people are going to get sick and die not long after they’ve been vaccinated – especially so when half of the human population of the planet has been vaccinated in a short period of time, starting with the elderly, disabled and immunocompromised.

And this is where our brains’ efficiency works against us. If someone gets sick soon after having a vaccine, our brains are wired to think that the vaccine caused the illness. Cause and effect. If it happens several times, that will only reinforce the idea, creating a self-fulfilling bias against the vaccine. But, statistically, the illness or illnesses probably had nothing to do with the vaccine – and that’s why we can’t rely on our perceptions or our “gut feelings” in these matters. We have to rely on peer-reviewed data, not Facebook or our friends’ anecdotes.

Oh, but, just in case, if Nick Cage is putting out a new movie, please avoid swimming pools while drinking.

Comments

Post a Comment